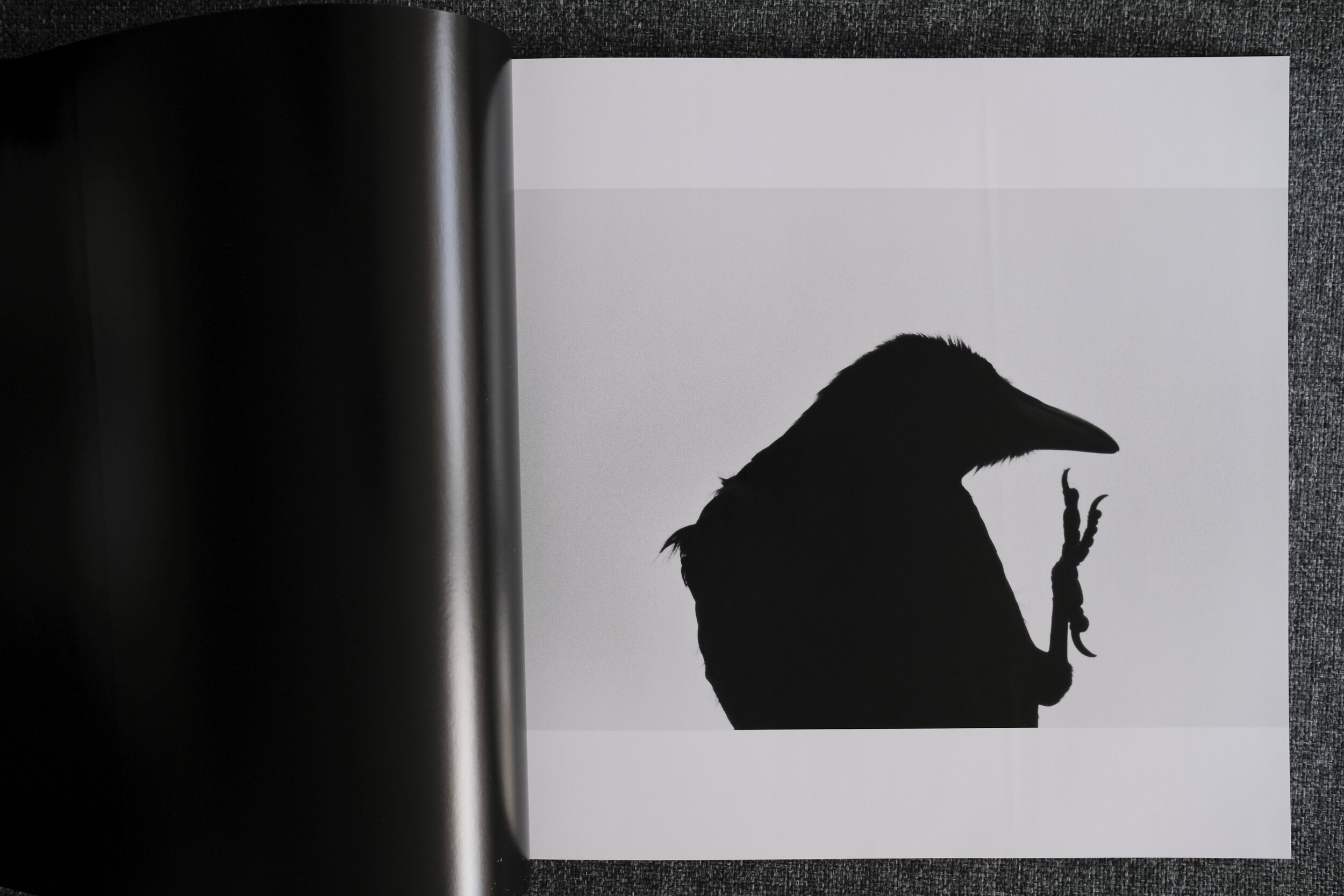

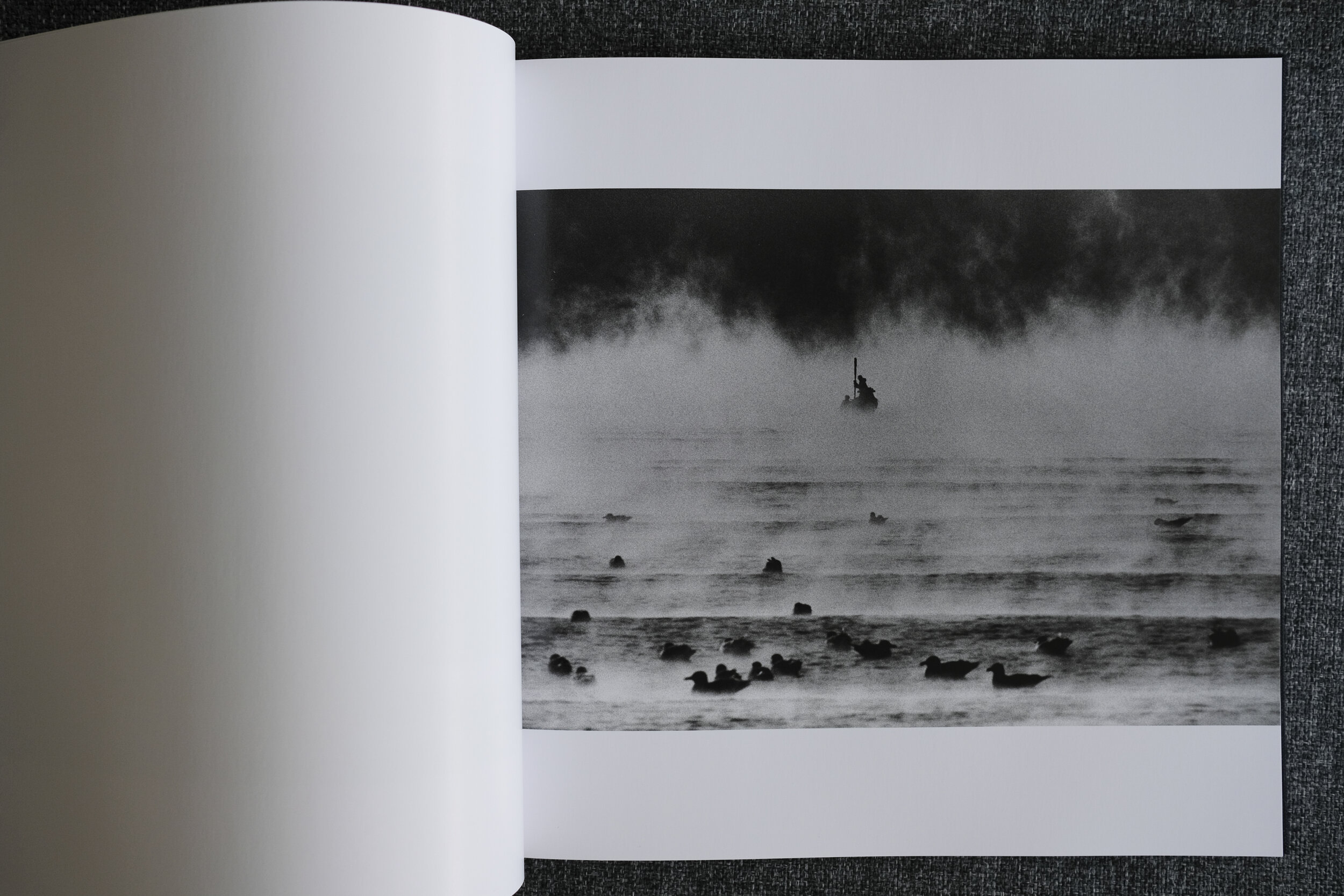

“Consistently proclaimed as one of the most important photobooks in the history of the medium, Ravens by Japanese photographer Masahisa Fukase was first published in 1986. Interpreted as a personal and political allegory for post-war Japan, it is a brutal yet beautiful story of love and loss.”

“Masahisa Fukase (1934-2012) is renowned for his obsessive, intense and deeply introspective photography through which he articulated his passionate and occasionally violent life. Fukase’s body of work is remarkable for the extraordinary range of visual perspectives that it encompasses.” (Michael Hoppen Gallery)

Fukase’s work has been exhibited widely at institutions such as MoMA, New York, the Oxford Museum of Modern Art, the Foundation Cartier pour l'Art Contemporain, and the Victoria & Albert Museum.

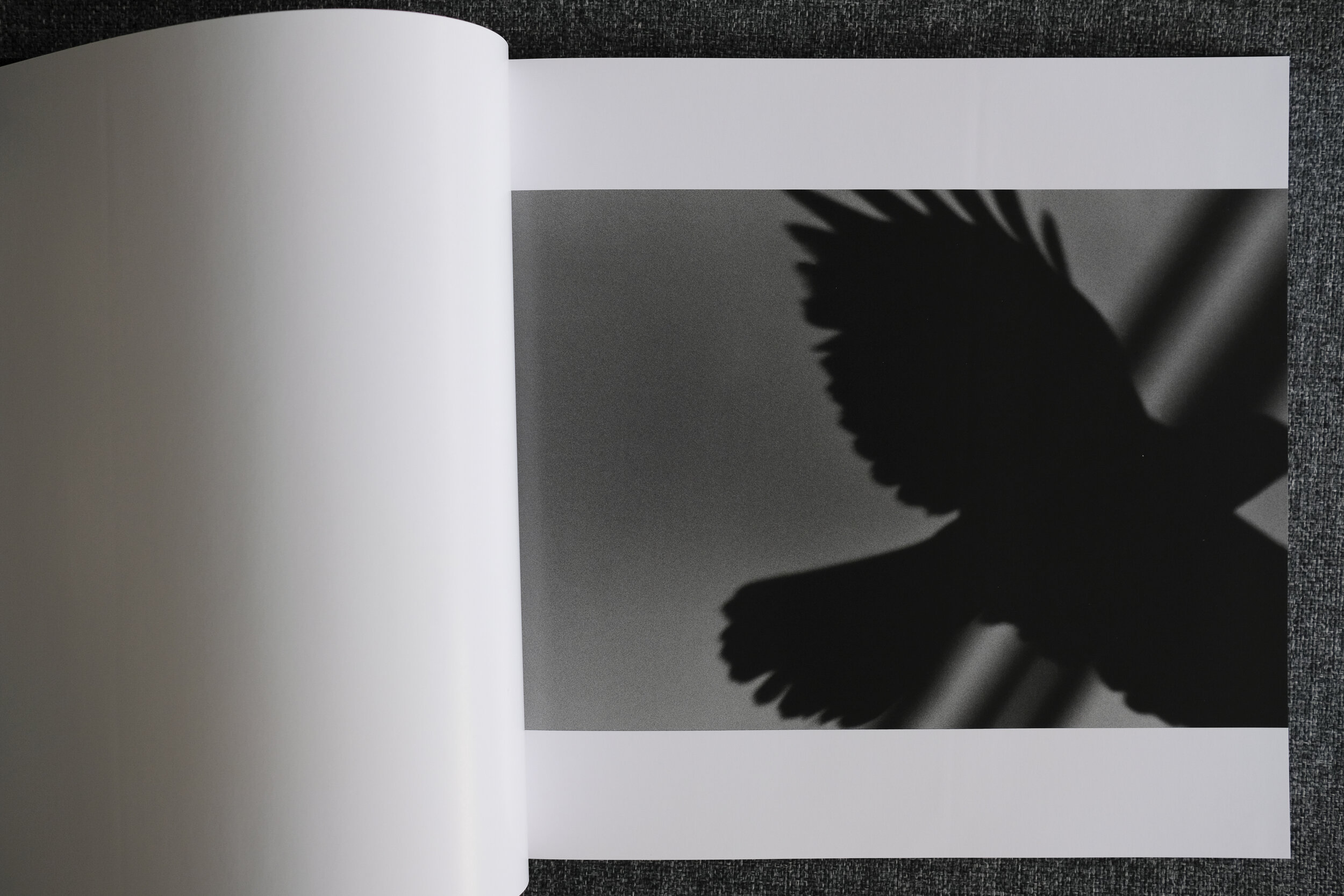

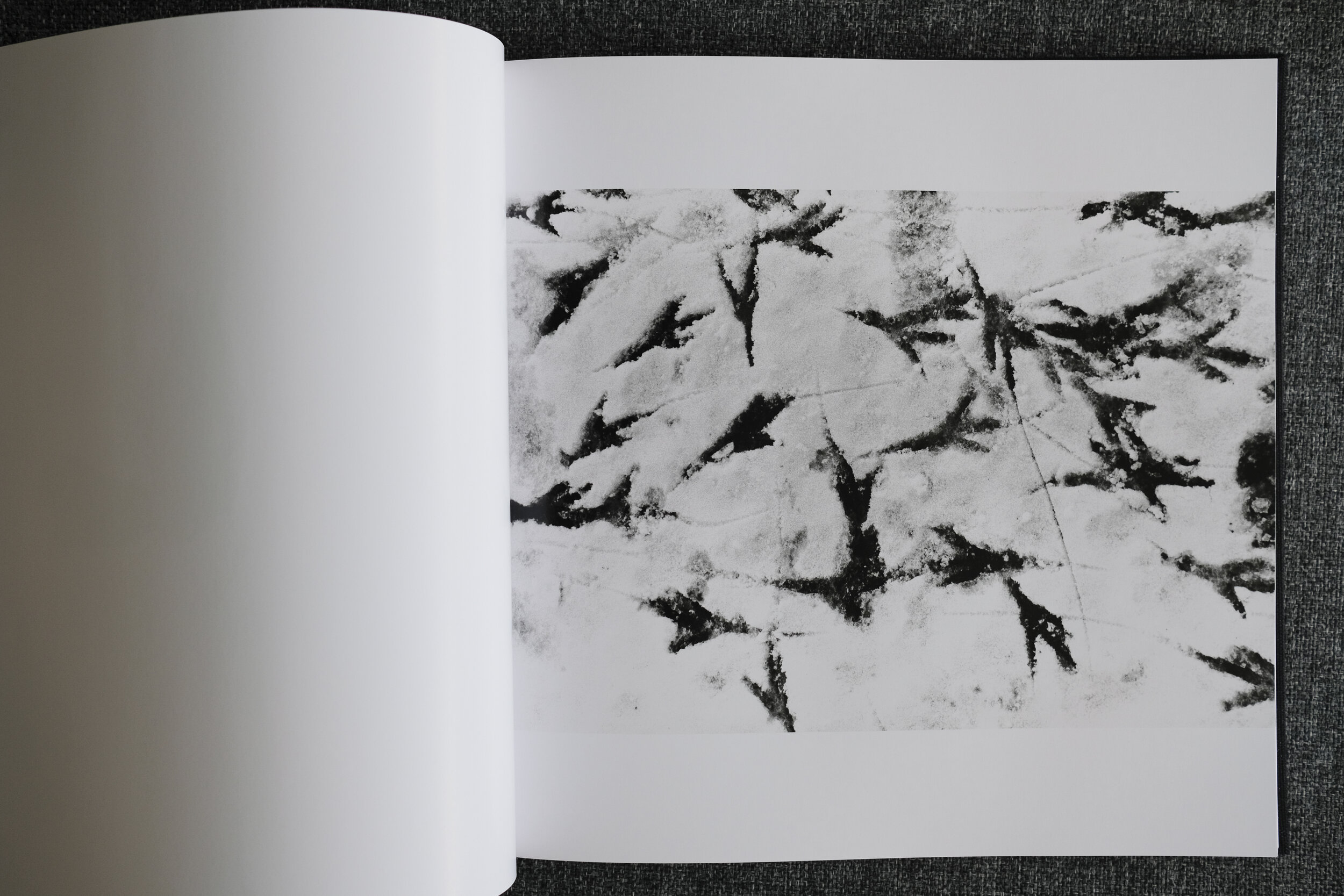

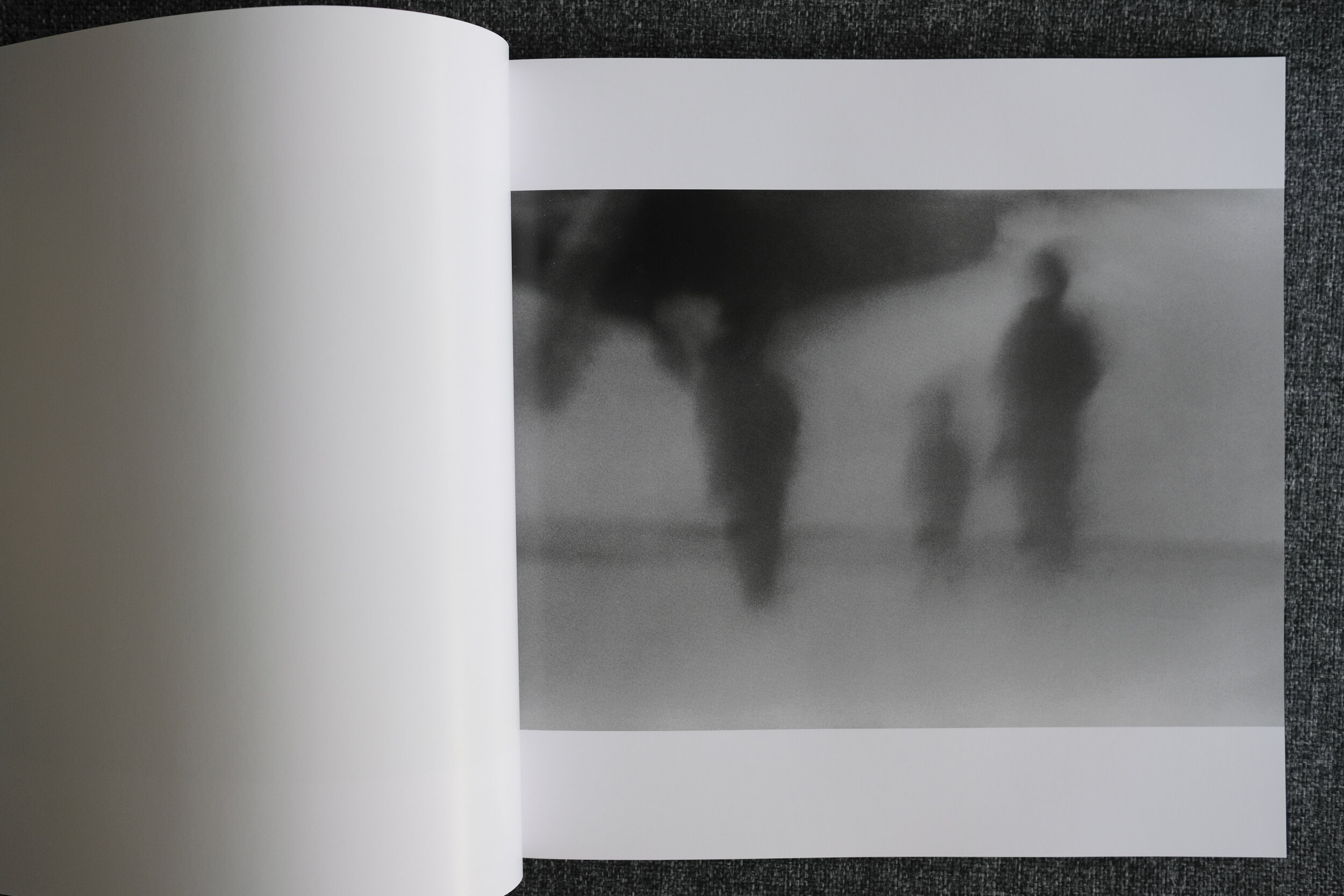

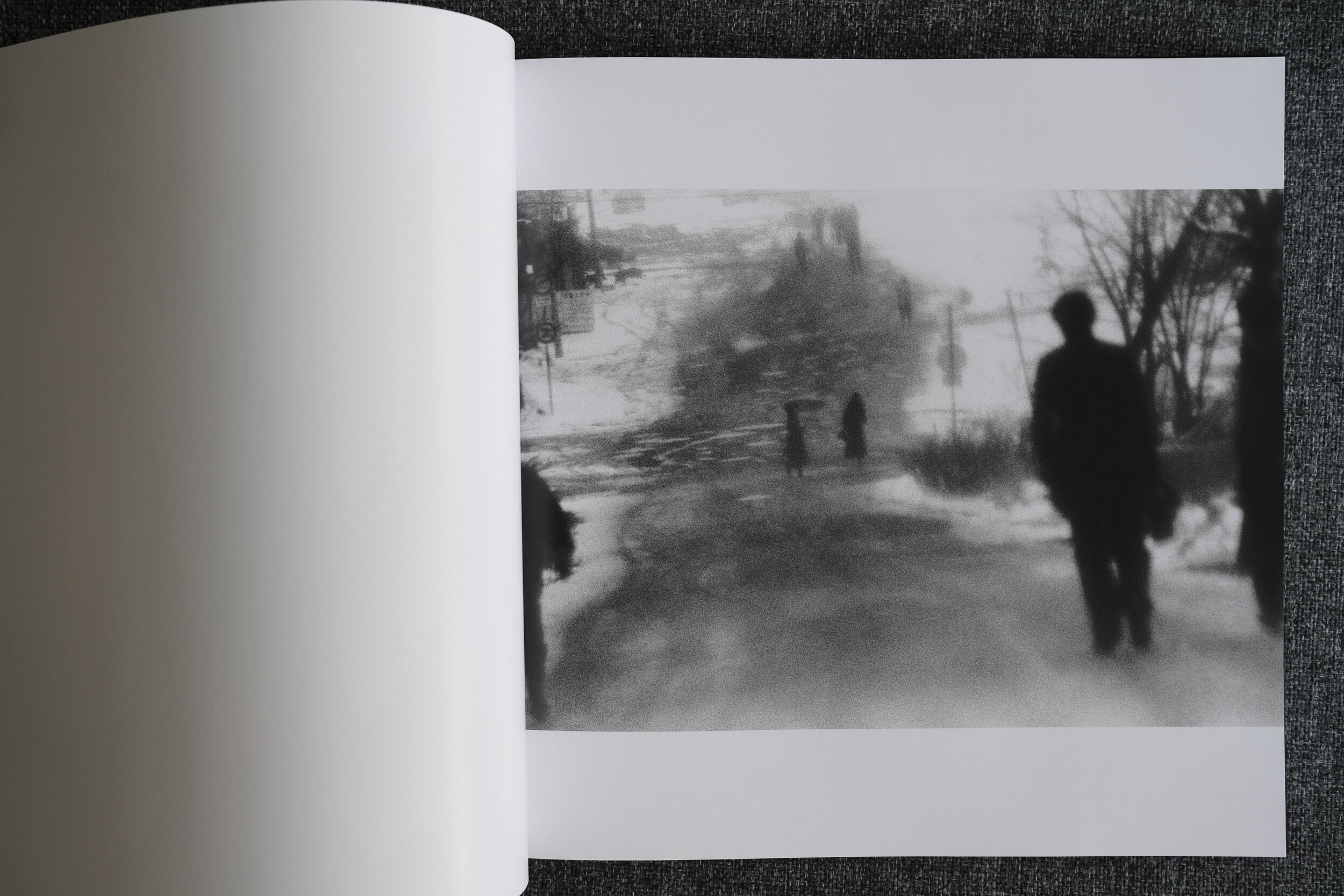

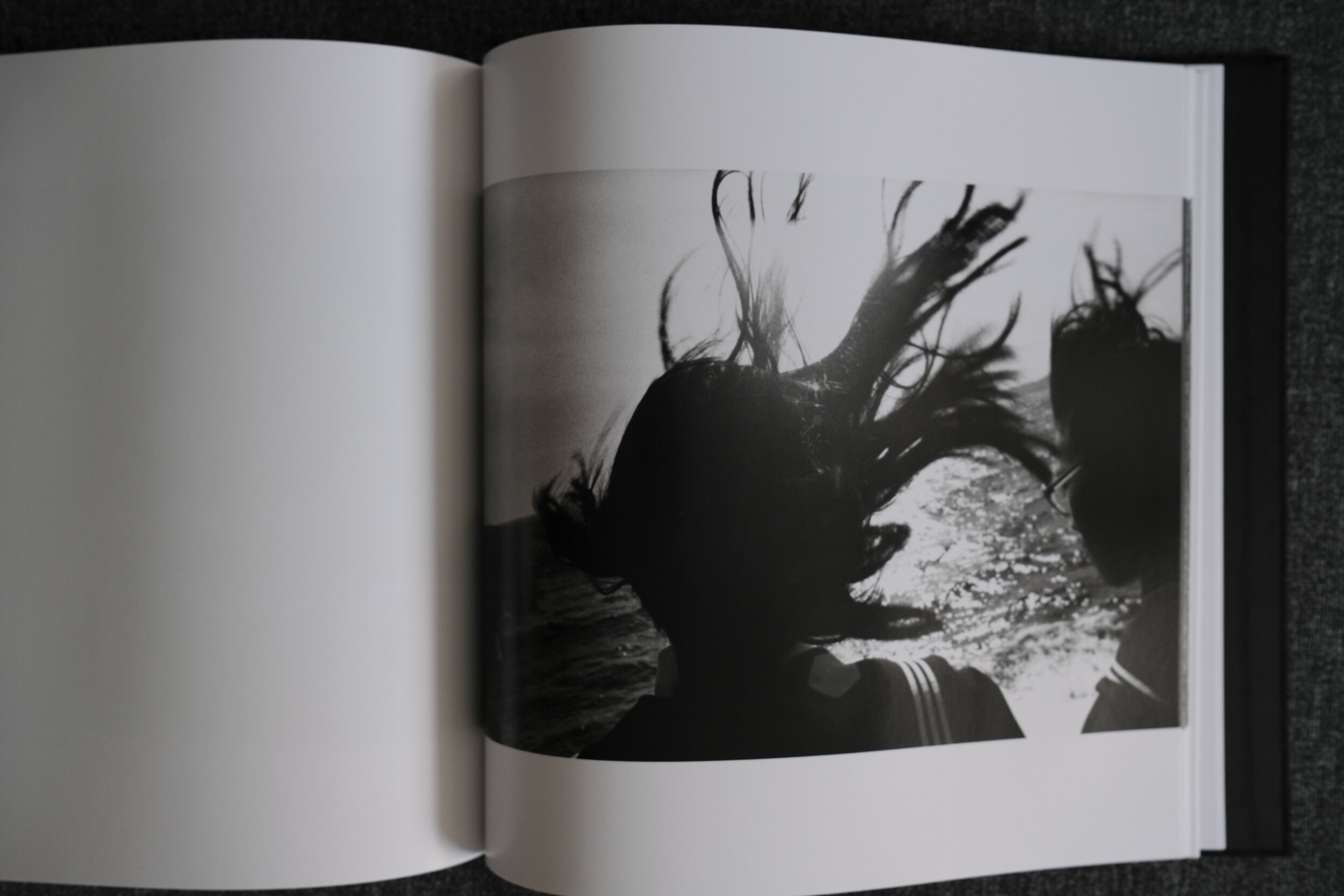

My own takeaway from what I have learnt about Masahisa Fukase is that he was a troubled artist who had difficulty relating to the world and to others and his photography became a search for self, at the expense of others including his wife and his marriage. He suffered from “existential angst and anhedonia” which “manifested in artistic self-identification with the raven and ultimately spiralled into a solitary existence and artistic practice on the edge of madness”. (Tomo Kosuga, Essay in Ravens, MACK 2017)

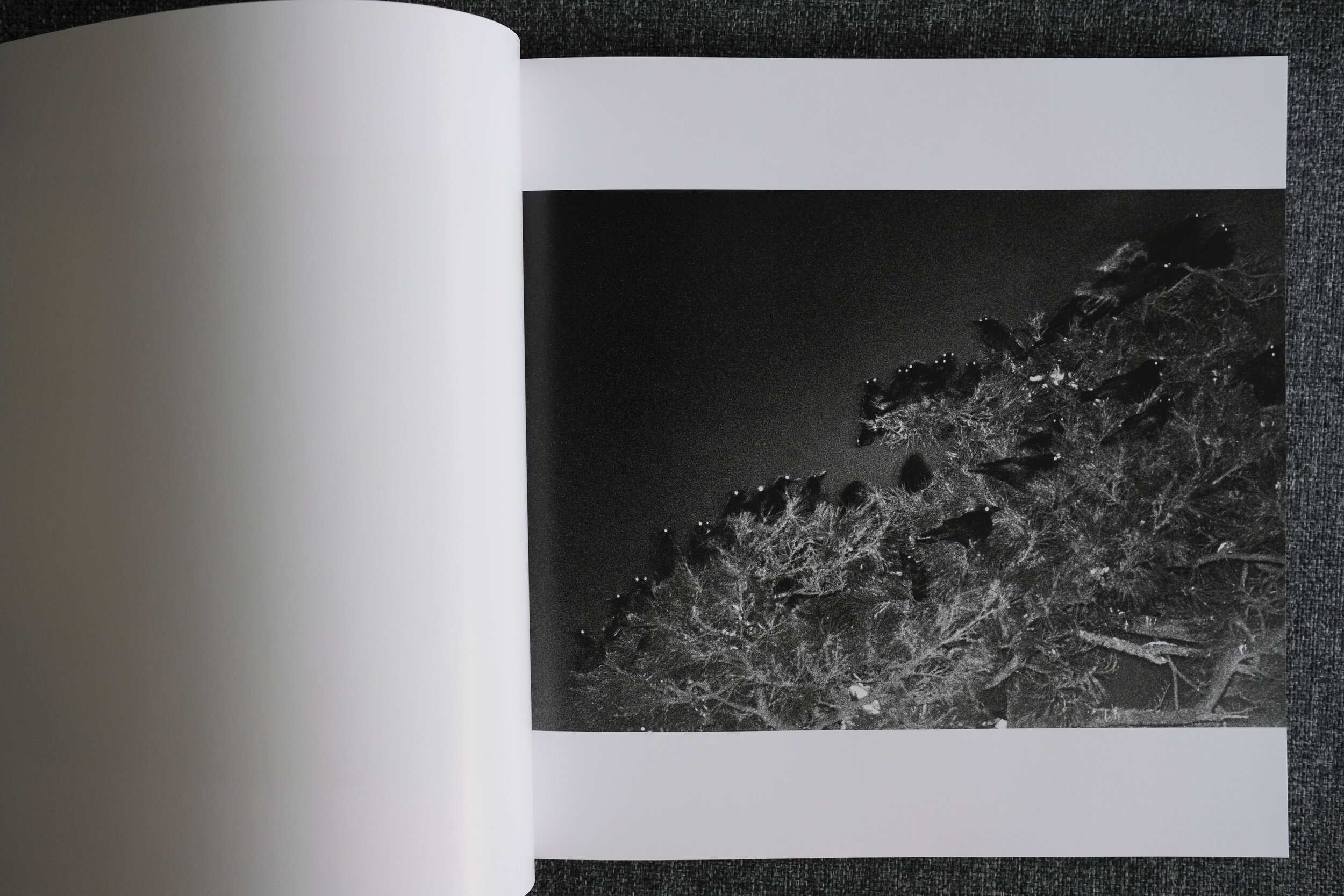

Born in 1934 in Hokkaido, Masahisa Fukase was the eldest child of a family who ran a family photography studio, which he was expected to take over. However, after he went to Tokyo to study photography, he became fascinated with the city and settled there.

Prior to Ravens, he had published two major books: Homo Ludence (1971), comprised of pictures of his troubled life over a ten-year period, and Yohko (1978) a book of his wife, made with painful perseverance through conflict and self-imposed separation. It was in the last period of his marriage with Yohko that be began work on Ravens.

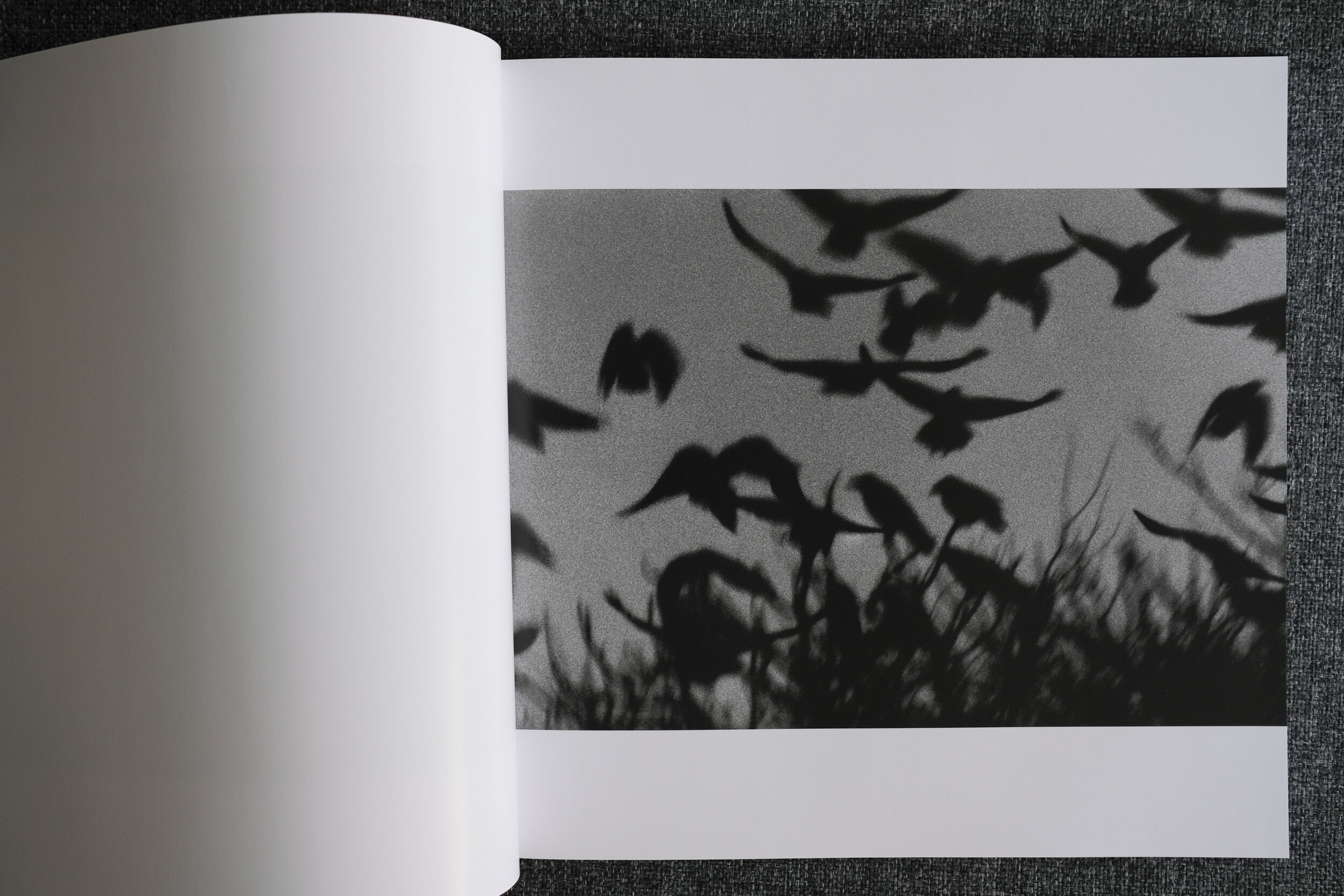

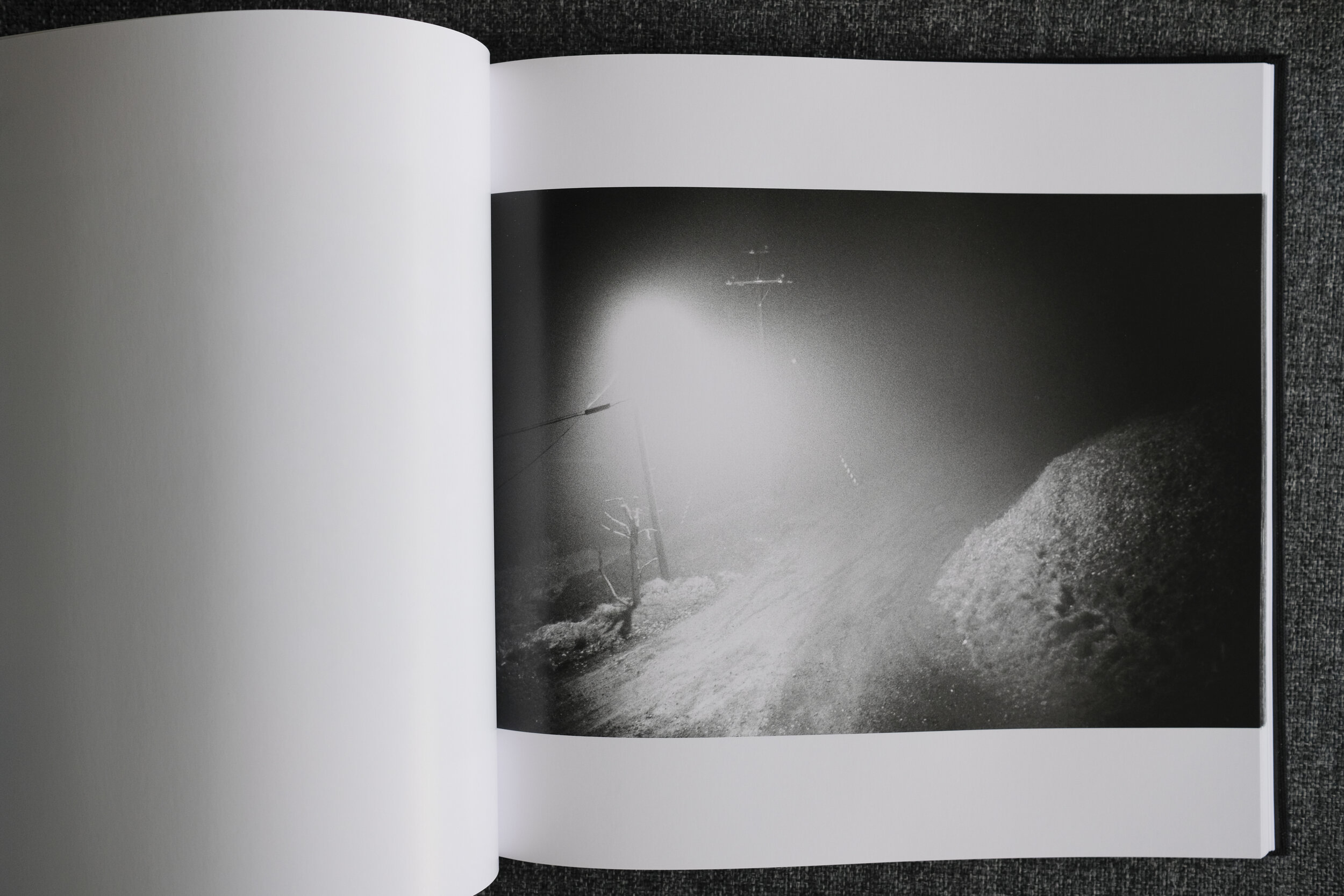

“The start of the series was a home journey to Hokkaido in 1976. He was forty-two years old at the time. His life was in tatters due to issues with alcohol and the imminent collapse of his decade-long marriage. Unable to handle the situation, Fukase left Tokyo in the hope of escaping his problems.” (Tomo Kosuga, Essay in Ravens MACK 2017)

Ravens was published in 1986. In 1992, only six years after its publication, Fukase fell down the stairs of his favourite bar and remained in a coma for the next 20 years until his death.

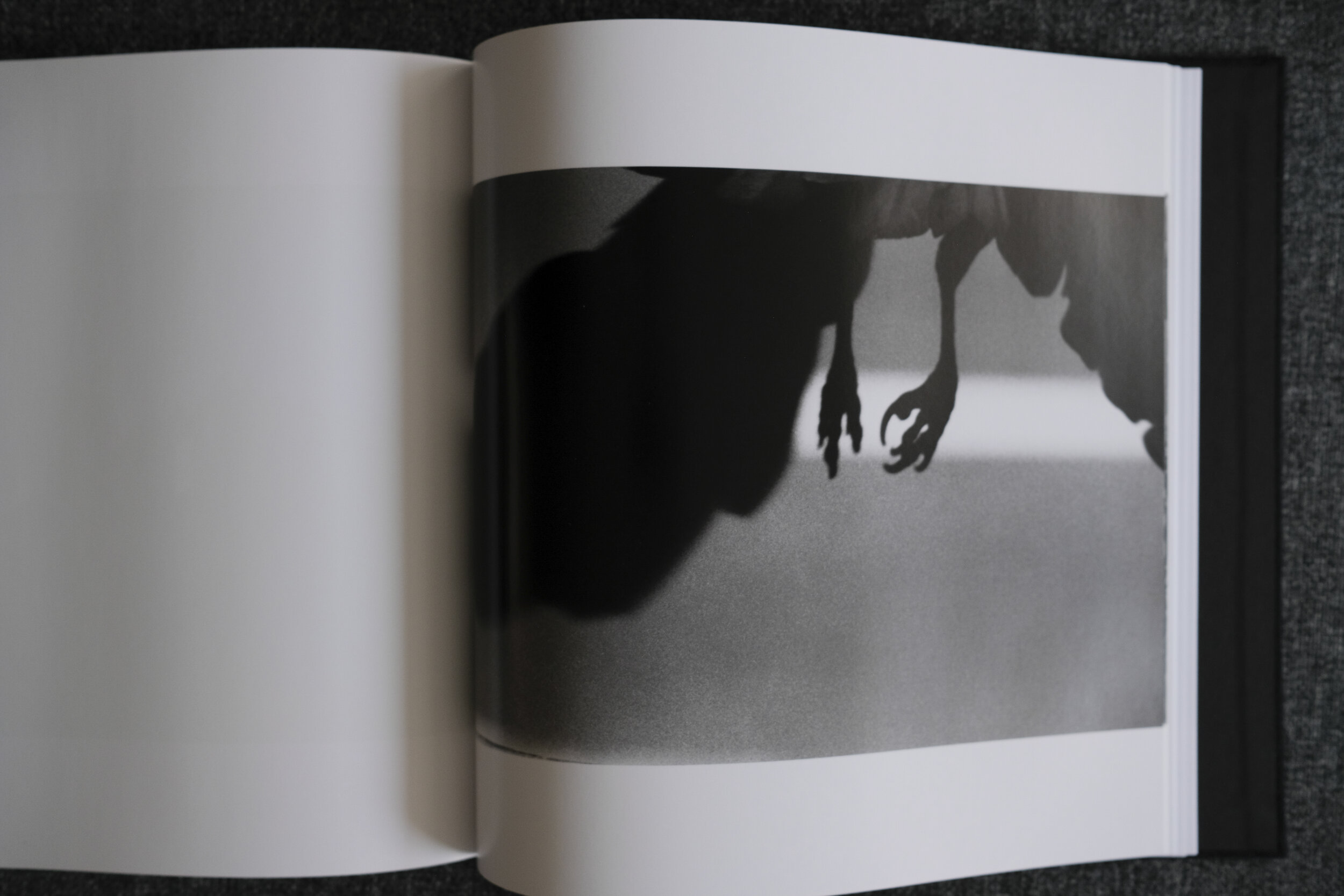

Brutal? Yes. Lonely? Unbearably. Especially when you know about the internal and external struggles of the artist. But in this work, there is also a kind of beauty. A beautiful exposition of isolation and intense pain. It is perhaps best summed up by Akira Hasegawa in the Afterword to the book:

“The world that Fukase occasionally captured was a form of hell. And, the artistry to form works of art out of hell is Fukase’s alone.”